By Violence Prevention Network

The Violence Prevention Network’s critical anti-violence concept, Anti-Violence and Competence Training, was developed specifically for dealing with violent young people who display extremist attitudes. This method is used as part of the Education of Responsibility in distancing and deradicalisation work. The programme strengthens clients‘ ability to question and reflect on existing patterns of justification and unconscious motives. In the case of a violent crime, the Anti-Violence and Competence Training also opens up ways of coming to terms with the past.

The trainers attempt to interrupt existing ideological chains of argumentation and deconstruct them together with the clients. This ideological debate often does not start with rational considerations, but with irritating elements, i. e. initiating contradictions and sowing doubts. This unsettling and questioning of „truths“ and extremist beliefs enables processes of openness and reflection. This demystification of extremist illusions can lead to the dissolution of patterns of justification that legitimise violence and extremism and lay the foundation for a critical reappraisal of actions. „It can only begin once the participants have established a relatively solid relationship of trust with the trainers (…), because it is not only a matter of meticulously describing the course of events, but also of questioning familiar strategies of justification and trivialisation, examining one’s own role within the group of accomplices and questioning the inevitability of what happened. Last but not least, it is also a matter of dealing with one’s own guilt and the feelings associated with the violent act that are triggered by the memory of the crime. In the further course of the programme, attention is drawn to the sometimes catastrophic consequences of the crime for the victim and their relatives, but also to the consequences for the perpetrator themselves and the people close to them.“ (Lukas 2006, 35f.) The trainers work with the clients to identify and clarify their underlying emotions.

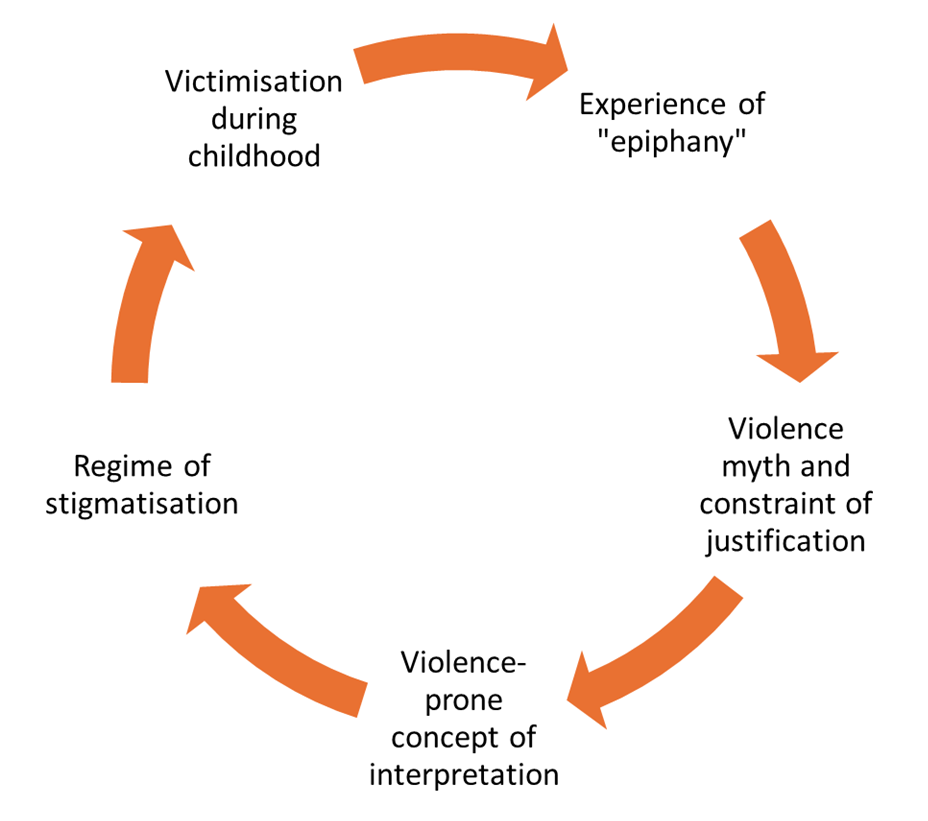

Radicalisation processes can, on the one hand, stabilise identity development and, on the other hand, lead to the legitimisation of violence. Clients‘ experiences of victimisation, such as feelings of helplessness, powerlessness, fear, despair or isolation, are often repressed and hidden behind a hard and emotionally cold shell. When they themselves resort to violence, they may experience feelings of power, recognition and respect; perpetrators describe states of consciousness that make them feel invulnerable. Violent behaviour is thus rooted in the repression of life experiences. Ferdinand Sutterlüty (Suterlüty 2002, 251) describes the development of violent careers in three strands of development, which do not necessarily form a chronological sequence, but do build on each other to a greater or lesser extent.

In the first strand of development, the adolescent victim becomes the perpetrator, switching from the role of victim to perpetrator and entering a new phase of life. The perpetrator may receive recognition and respect from their social environment for this, which can lead to a new self-image among young perpetrators.

Violence-prone interpretation regimes describe the second strand of development in a career of violence according to Sutterlüty. Perpetrators perceive certain situations through the lens of (unconscious) individual interpretation patterns and often interpret violence as the only solution. They repeat what they are familiar with from home or from their childhood. However, they no longer want to be victims; instead, they defend themselves and pre-empt supposed perpetrators.

The third strand of development focuses on the experience and consolidation of self-perpetrated violence. The normative ideals and self-image of young perpetrators lead to moments of ecstasy and power. This has consequences for their self-image and self-perception. High expectations and the glorification of violent acts soon lead to negative consequences, such as stigmatisation in their private lives, repressive measures at school or work, and far-reaching criminal consequences.

The cycle of violence (Mücke 2014a, 165 + Mücke 2014b, 271) provides a way of recognising patterns of violence in people’s life stories:

Figure 1: The cycle of violence

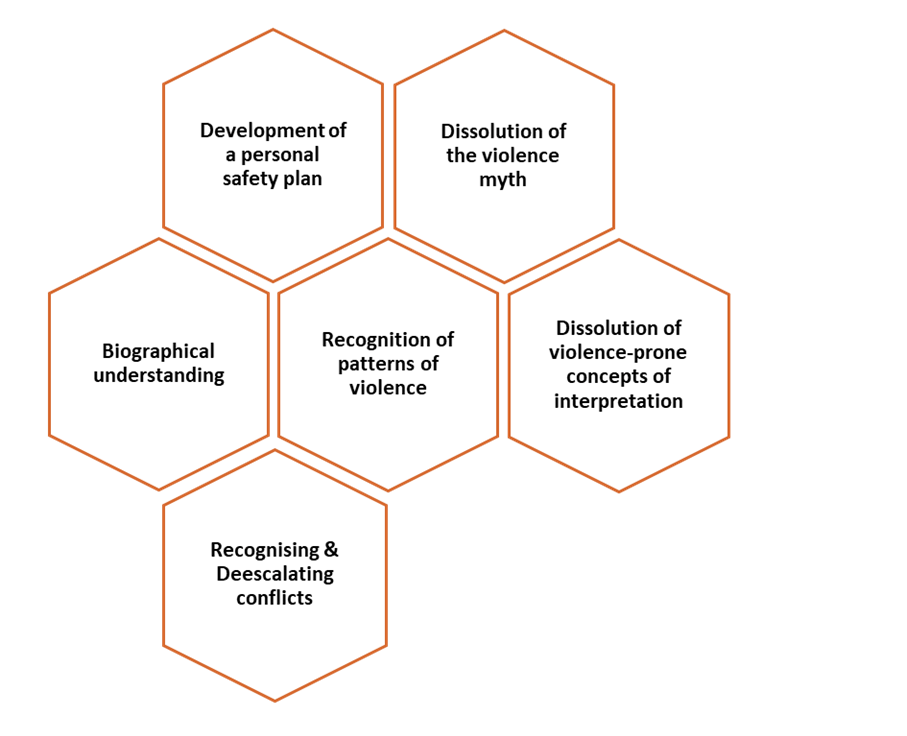

Those who can reflect on and deal with their feelings competently improve their ability to control their own negative impulses in a constructive and future-oriented manner. This is to be achieved by understanding situational violence and violence careers, by coming to terms with violent acts and by learning conflict resolution strategies.

Figure 2: Building blocks of the Violence Prevention Network’s Anti-Violence and Competence Training

The so-called „violence sessions“ are part of the Violence Prevention Network’s distancing and deradicalisation work. In such a session, clients voluntarily talk about their actions and their own history, which can take up to three hours. During this time, the trainers try to listen without preconceived opinions or judgements. Clients often describe their actions as a legitimate response to injustice. The trainers question these subjectively interpreted instances of discrimination and the perpetrators‘ victim mentality.

The crime is then examined and reconstructed from other perspectives. The behaviour and actions of the victims, accomplices and witnesses can be re-examined, initial contradictions in the lines of reasoning and personal memories can be uncovered, and reactions to these can be analysed. The trainers conduct this conversation very carefully and show themselves to be interested yet neutral discussion partners – especially when very negative or violent situations and actions are described, as this can be just as stressful for the narrators as it is for the listeners. Critical reflection on past actions requires close examination, the removal of mental blocks, and the courage to talk about them and put one’s own emotions into words. Therefore, it usually takes more than one „violence session“ to first work through the crimes and reflect on experiences of powerlessness and the past, so that responsibility for the actions can finally be taken in a final step.

Standards of the Anti-Violence and Competence Training

All Violence Prevention Network trainers complete a training programme developed by Violence Prevention Network during their first year with the organisation. The training curriculum is a twelve-month part-time programme consisting of nine teaching/learning modules. The respective training units impart knowledge about the psychosocial dynamics underlying violence and the processes of ideologisation and radicalisation and enable participants to act confidently when dealing with ideologised and radicalised individuals. This is because working with the target group focuses on addressing violence and its ideological integration.

Training objectives

– Enabling participants to deal with inhuman ideologies and prejudiced arguments

– Learning how to build working and communication relationships with clients and their social environment

– Ability to practise non-violent conflict resolution strategies

– Understanding situational violence and the development of violent careers through „biographical dialogue“

– Learning about different methods for dealing with acts of violence and political education work

– Activating resources and strengthening social skills to develop a non-violent personal future

Anti-Violence and Competence Training modules

– Unlearning violence through insight processes and appreciative working relationships

– Biographical understanding

– Analysis and understanding of the career of violence

– Development of empathy towards oneself

– Promoting emotional skills

– Dispelling the myth of violence through cost-benefit analysis and visualisation of the personal stop card

– Dispelling patterns of justification

– Recognising one’s own patterns of violence using non-confrontational, investigative, unsettling techniques

– Dismantling the violence-prone interpretation regime through current conflict management, personal violence reconstruction and educational work

– Provocation test: Practising non-violent and confident conflict resolution

– Recognising and de-escalating conflicts

– Developing a personal safety plan that considers personal resources and individual risk factors

Taken from: Violence Prevention Network (2021). Schriftenreihe Heft 7. Erfolgreiche Distanzierungs- und Deradikalisierungsarbeit – 20 Jahre Verantwortungspädagogik entwickelt von Violence Prevention Network, S. 18 – 21

Literature:

Mücke, Thomas (2014a). „Verantwortung übernehmen – Abschied von Hass und Gewalt“: Coaching für ideologisierte jugendliche Gewaltstraftäter. Das Konzept der Präventionsarbeit: Verantwortung übernehmen, in: Farin, Klaus (Hrsg.) (2014): Kerl sein. Kulturelle Szenen und Praktiken von Jungen, Berlin, S. 163-181.

Mücke, Thomas (2014b). Rechtsextreme Radikalisierung – biografischer Kontext und pädagogische Interventionen, in: Brockhaus (Hrsg.) (2014): Attraktion der NS-Bewegung, Essen, S. 269-278.

Sutterlüty, Ferdinand (2002). Gewaltkarrieren. Jugendliche im Kreislauf von Gewalt und Missachtung, Frankfurt am Main, New York.