By Niklas von Reischach (Violence Prevention Network)

This article was first published in German in: Interventionen #19, 2025 by Violence Prevention Network

Calls to terrorism are more than just messages motivating people to commit acts – they are also aestheticised acts of communication. As a result, insights into the strategies of terrorist groups and the potential effects on recipients can be derived from their deliberately designed messages. Extremist actors often use so-called stock photography, i.e. images that are pre-produced by professional agencies or amateur photographers on platforms such as Flickr or Shutterstock to cover as wide a variety of topics as possible so that they can be used for videos, presentations or websites. The images are offered by these agencies for a fee or made available free of charge on the internet. The images created in these contexts are not intended to have any specific meaning, but rather to provide a general visual context (e.g. a meeting/phone call/performance is depicted in an abstract way), save users time and money, or provide variety. But why do extremist actors exploit such images, which are also used by companies and other customers of large image databases? What aesthetic strategy do they hope to achieve with this? Why are they interesting to these actors and their target group? What happens to the images in this context?

This article analyses a digital image-text combination[1] of a call to terrorism from the perspective of media aesthetics and image science. In this article, aesthetics is understood in the sense of aisthesis as an „event of sensory perception“[2] (Baßler/Drügh 2021, p. 10), in which „an intellectual processing of the sensory given takes place with the involvement of emotion“ (ibid., p. 19). Consequently, contrary to the commonly used interpretation of the term, aesthetics is by no means understood artistically or as a synonym for ‚beauty‘ (Goppelsröder 2022, p. 16). In this article, a media aesthetic analysis refers to an investigation of all kinds of sensory perceptions that arise through interaction with digital media (Imort/Müller/Niesyto 2009 after Zacharias 2012/2013, p. 3). Based on a qualitative examination of a call for terrorism that was publicly discussed in early 2025, this article focuses on the interpretation of potential sensory perception effects that can arise when viewing corresponding multimodal productions, in this case expressed through text and images. Building on this, conclusions are drawn for the prevention of extremism.

Strictly methodological approach for dealing with sensitive images

The call to terror is examined using the method of political iconography (Schneider 2014). This approach focuses on the effects of images on individuals and social groups and is based on the premise that the objects of analysis actively participate in political and social processes and are produced for this reason. Images are to be understood as „active objects“ (ibid. p. 335) that intervene in current political events and can even direct them (Warnke 2010, p. 72). Terrorists in particular are said to consider the importance of the aesthetic dissemination of their actions. This includes not only the media dissemination of their deeds, but also other deliberately chosen aspects such as outfits worn during the commission of violence, the soundtracking of deeds through the dissemination of appropriate musical set pieces, or direct references to gaming aesthetics. The official production and dissemination of images by governments and government bodies are also subjects of political-iconographic analysis (see Kaupert/Leser 2014). Central to Richard’s shifting image method are motif migrations; a motif can also appear in a similar form on TV, in print or in other digital images. The meanings of a digital image are variable and inconsistent in the sense of the shifting image concept (Richard 2003) and arise in relation to other motifs, some of which are published simultaneously. The following analysis therefore includes additional images in order to elaborate on the content of the collage.

Furthermore, this approach focuses on the materiality (e.g. colours, grain, or shapes) of the image and considers forms of power and society. According to this method, the image analysis is carried out in three steps: 1) a pre-iconographic description, 2) an iconographic analysis, and 3) an iconological interpretation. This means that, in a first step, the image is described concisely, and the factual and expressive elements are identified on the basis of the analyst’s life experience. In a second step, meanings are attributed to the motifs. The motifs represent abstract content. In the sense of image science analysis (see below), we refer to these as images. In order to grasp this abstract content, it is necessary to move away from the concrete description of the image and extend the scope of investigation to the discursive environment in which the images are found e.g. by including texts, other images, videos, etc.

Based on the first two steps, a third step involves interpretation. The meaning or content of the object of analysis for a period of time or culture is worked out. In this step, image similarities to other images are subsequently identified (Schneider 2014, pp. 331-335).

Central to the scientific analysis of images is the distinction between a picture and an image. A picture is a material object, whereas an image is an abstract, mental entity that transcends media and can be evoked in the mind simply by mentioning a term or recognising a visual motif. In the present case, insights into the media aesthetics of calls to terrorism are thus gleaned from a picture (the combination of image and text). This contains images that may also appear in other images or narratives (Mitchell 2009, pp. 321-323).

Description

A pistol pointed at the viewer, clutched tightly by a hand reaching out of the darkness (Fig. 1): a low angle shot, a strong contrast between light and dark, a view into the barrel of the weapon from below and at an angle. A victim’s perspective or a focus on the powerful hand is suggested. Behind it, a person is vaguely visible. Above it, the words „DON’T WAIT FOR A NEW YEAR TO TAKE ACTION!“ are emblazoned in white lettering. Below are the names of ten events and festivals in Europe and the USA, each under a crosshairs in bright red. The collage suggests an imminent violent event, with shots seemingly about to be fired. This is indicated by the pistol pointed at the viewer, the crosshairs and the last word of the slogan, which is typographically emphasised by its size: „Action!“. The font also conveys a sense of temporality; the materialisation only takes place towards the bottom. The typography thus picks up on the approaching event.

Contextualisation

This image-text combination of the so-called „Islamic State“ (IS) was published by the Terrorism Research & Analysis Consortium (TRAC) on 12 January 2025 on its X profile (@TRACTerrorism (x.com)). TRAC writes analyses about terrorists based on one of the world’s largest databases (trackingterrorism.org). In the days that followed, various media companies reported on it, including BILD newspaper (see Schneider (bild.de)) and Kronen-Zeitung (see Ramsauer (krone.at)). The history of the reception, i.e. the way in which the event is taken up in other contexts, is decisive for the aesthetic effect here. On the one hand, this contextualisation by TRAC makes the motif appear threatening: the barrel of the pistol, slightly offset to the right, is aimed quite precisely at the viewer. On the other hand, the image is inconspicuous for a call to terror, as it uses stock photography. This is image material that was not produced for a specific audiovisual product, but rather with a view to its potential for use in various contexts. This material often has a (commercial) generic-professional look (cf. Scherer et al. 2021).

Analysis

Against this background, two essential observations lend themselves to analysis: On the one hand, the media-aesthetic significance of the collage arises from the terrorist context. The contribution can thus be linked to other visual materials that incite terror. On the other hand, the collage must be analysed in terms of its use of stock photography. Here, a lack of generic specificity is deliberately pursued or accepted: stock photography is designed to remain easily usable for as many different purposes as possible so that it can be sold as often as possible. Based on these two observations, contextual knowledge must be developed in order to interpret the content of the image-text combination.

The TRAC contextualisation as terrorism makes the image compatible with other common terrorist aesthetics. The collage is reminiscent of similarly structured image-text configurations from the phenomenon of right-wing extremism, specifically the right-wing extremist media aesthetics of Terrorwave circulating in isolated forums.[3] Subcultures existing on the Telegram messenger service encourage violence with visual aids, for example by calling for attacks and glorifying right-wing extremist terrorists. The design methods used create subcultural cohesion by glorifying militant appearances. Terrorwave first appeared around 2018 and is usually characterised by glitch[4] , and retro aesthetics; while neon colours or black, white and red are also characteristic. This style often features historical images of masked male guerrilla fighters with machine guns or fascists, skull masks and right-wing extremist symbols. Figure 2 shows an example of an image with terrorwave aesthetics in glitch and retro style.

Terrorwave is characterised by a void in terms of the consequences of the glorified violence. Corresponding image practices express a style that directly references contemporary fashion aesthetics, while omitting the ideological affiliation of the activists. There are no extremist logos or slogans, so that the images can circulate in mainstream networks. Images with corresponding aesthetics and motifs express young men’s longing for terrorist violence. Terrorist acts are glorified – mostly in English – through stylish presentation. (Molloy 2023 (gnet-research.org), Terrorwave (belltower.news), Manemann 2021 (belltower.news))

Furthermore, the collage image appears to have been created using stock photography. This type of image is designed for commercial use and is tailored to the wishes of its customers. Stock photography is freely available online, meaning that terrorist actors can purchase or appropriate such material. Due to the dynamics of the internet, it is also no longer de facto protected by copyright, as it can often be screenshotted and forwarded on social media and other forums. Anonymous actors appropriate any material they find attractive; image rights no longer play a role in these contexts. This means that stock photographs also come into circulation for which not everyone pays.

Even outside of terrorist contexts, this results in remarkable coincidences that point to a possible reception: the parties Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Alternative for Germany (AfD), for example, used the same images in political campaigns. Since their inception in the 1970s, image databases for photography have focused on advertising. Therefore, high image quality is crucial, and their aesthetics can be associated with a „sterile perfection“ (Nolte 2024, p. 41). In addition, the aesthetics of stock photography are generally characterised by a tension that arises, on the one hand, from their „generic, open-ended and anonymous“ (ibid., p. 20) presentation. Stock photography should systematically hide details, remain vague and open to interpretation so that it can be used in a variety of ways. It should avoid „any form of individual distinction“ (ibid., p. 21).

On the other hand, stock photography aims to achieve a „singular quality and obvious originality“ (ibid., p. 20) in order to entice potential customers to buy. Furthermore, the aesthetic content of stock photography results in particular from its interaction with language. Language attempts to limit the aforementioned excess of meaning. Ultimately, this form of imagery can be described as inconspicuous, allowing stock photographs to blend into their surroundings as discreetly as possible (ibid., pp. 7/10/16/20/22/43). Stock footage aesthetics are also frequently criticised on ethical grounds in other contexts, e.g. because they make people appear interchangeable and de-individualised (Frosch 2020; 2003; Kalazić et al. 2015; Aiello 2022). Since stock photographs are characterised by the features mentioned above, they provide terrorists with a supposedly neutral projection surface that is overlaid with new meanings in an ethically problematic way and integrated into their own aesthetic communication strategies.

Interpretation

The media-aesthetic content of the present image-text combination must be developed based on these two derivations in particular.

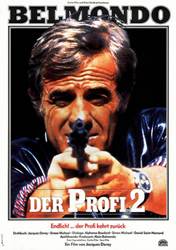

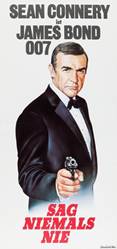

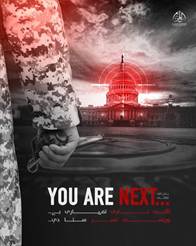

Like the visual practices of Terrorwave, the present collage glorifies and heroises violence through its martial presentation, while omitting the consequences of an attack. The motif of the weapon signals not only a threat but also strength, power and control. No injured people, no blood and no dead bodies are visible. Terrorist actions are to be upgraded in the spirit of Terrorwave with the help of nonchalance.[5] The imagery is intended to display „tacticool aesthetics“ (Molloy 2023). This calm and measured staging creates visual similarities to film posters from (Western) cinema culture. The posters for the films „The Professional 2“ (Fig. 3) and „James Bond – Never Say Never Again“ (Fig. 4) also use a gun pointed at the viewer to promote the film with a suspenseful motif. Terrorists thus present themselves as action heroes in this appeal. The aim is to elevate the status of perpetrators of terrorist attacks with the help of this combination of images and text. It is revealing in this context that a first-person shooter perspective is created solely by the crosshairs; the perpetrators themselves and a gun pointed at the viewer are more dominant. As with the film posters, the actor is thus also visually at the centre of attention. In this respect, the collage analysed in this article differs from other calls to terrorism (cf. e.g. Fig. 5).

Fig. 3, 4, 5

Furthermore, in the sense of Terrorwave, no clearly recognisable ideological affiliation can be found in the call analysed (only on closer inspection can an extremely small and indistinct logo be found in the lower right-hand corner). The use of English and the avoidance of Arabic means that the collage is not clearly recognisable as a call to terror by so-called “Islamic State” („IS“).

The image of the call to terror eludes any form of individual distinction. It is kept open on a visual (and linguistic) level, thus avoiding an immediate perception of threat. No person clearly recognisable as a so-called „IS“ fighter is holding the weapon. This inconspicuousness of the collage means that its threatening legibility can be understood without contextual knowledge and without processing by the viewer. The much-cited motif of a pistol barrel pointed at the viewer can be found, for example, in an Instagram post by Radio Berlin-Brandenburg (rbb) (Fig. 6). In this context, the public broadcaster’s post reports on Berlin’s crime statistics. The generic openness of the image material used in the call to terror is therefore also intended to prevent it from delegitimising itself in the flood of images on social media. This aesthetic strategy means that the call to terror achieves a wide reach. The call to terror can thus circulate in popular social networks in the sense of a meme, and only the revelation by experts leads to its discrediting and to an urgent, tense and violent perception.

The high quality of the image makes it suitable for use in stock photography. The specific quality of the image reveals a technical solidity that can be measured, for example, by the lighting of the image, coupled with a creative restraint that reveals no personal positioning whatsoever. This also allows the producers to express a feeling of strength and dominance. The low threshold for acquiring image material on the internet enables terrorists to avoid appearing as impoverished guerrilla fighters and to create a professional self-image. When viewing the call to terror, the perception may arise that the terrorists are part of a meaningful movement. As a result, in addition to its call to terror, the collage is also effective as propaganda material, and the actors presumably want to maximise the impact by spreading calls to terror through journalistic media, among other channels.

Similar debates are being held in relation to actions by the new right-wing Identitarian Movement: in 2016, the actors climbed the Brandenburg Gate, whereupon numerous media outlets reported on it, thereby unintentionally spreading their iconography (Barthel/Begrich 2017, p. 15). A search engine query illustrates how easily this professionalism can be simulated in the present collage. Figure 7, for example, is the result of a quick search engine query. Using the keywords „stock photo“, „gun pointing at viewer“ and „dark“, it is easy to find similarly professional images.

Conclusion

This collage should be understood as an active object that presents terrorism in an emotionally appealing way. Images freely available on the internet allow terrorists to stage terrorism in the style of a James Bond film and glorify violence. Without contextualisation, the image material is only moderately disturbing; it camouflages itself by expressing a New Year’s resolution and inconspicuous imaging practices, thus evading detection by content filters in the course of selection by artificial intelligence.

This glorification of strength can be particularly attractive to young, disoriented people. It can help young people who are already struggling with feelings of anger, exclusion or disorientation in their search for identity. This group could be more strongly attracted by an aggressive and at the same time ‚cool‘ symbolism, as it picks up on their emotions, breaks down inhibitions and catalyses disorientation into a supposedly meaningful action. The slogan „Don’t wait for a new year to take action!“ and a gun pointed at them convey urgency and explicitly call on them to take action.

Extremism prevention must respond to such aesthetic strategies by promoting media literacy among young people through primary preventive measures, for example. In addition to disturbing calls for terrorism, this media literacy must also focus specifically on inconspicuous image practices that connect to everyday experiences such as film or gaming. In addition, individual counselling should be provided to young people at risk, who are in danger of consuming or disseminating such calls. Vulnerable young people must learn to recognise extremist messages and, where appropriate, to respond to them in a resilient manner. They must understand the strategies used to stage a ‚martyr’s‘ death in order to remove the taboo surrounding (mass) murder.

Furthermore, reactive approaches must be pursued when radicalisation has already taken place. Clients who have consumed such propaganda need space to talk about their feelings. It is important to take their fears, anger and desires seriously and channel them into constructive avenues. Specific content should be addressed. Counsellors should talk explicitly with clients about the message of the material: who produces such material, what are the creators‘ goals, what personal consequences would arise following their calls? This also requires new methods of emotion-oriented work with the material in order to work out together with clients in individual cases why certain media messages are specifically appealing and attractive to them and what other opportunities for identification outside of extremist contexts could fulfil a similar function.

The highly dynamic and fast-paced nature of the media aesthetics used in extremist terrorist appeals requires those involved in preventing extremism to continuously engage with the changing forms of communication in the digital space. Ongoing monitoring is essential in order to identify current developments at an early stage and respond appropriately. This requires close and coordinated cooperation with advise centres, educational institutions, youth centres, families and investigative authorities in order to implement preventive measures effectively and in a context-sensitive manner.

Author

Niklas von Reischach received his doctorate from Goethe University Frankfurt am Main in the interdisciplinary research project Contemporary Aesthetics – Categories for Art and Nature in Alienation. His doctoral thesis, Desinformationen als journalistische Glitches – Visuelle Sabotagen und postdigitale Ästhetiken der Alternativen Rechten, will be published by transcript Verlag in 2026. He has been working in the Digital Department of Violence Prevention Network since July 2024.

Literature

Barthel, Michael, and David Begrich. 2017. „Aesthetic Mobilisation. The media strategies of the new right pose new challenges for journalistic reporting.“ miteinander-ev.de. Accessed 28 May 2025. https://www.miteinander-ev.de/…Kulturkampf-von-rechts.pdf. [Link no longer available].

Baßler, Moritz, and Heinz Drügh. 2021. „Contemporary Aesthetics.“ 2nd ed. Konstanz: Konstanz University Press.

Goppelsröder, Fabian. 2022. „Aisthesis in the age of digitalisation.“ In: Aesthetics of digital media – Current perspectives, edited by Martina Ide, 15–30. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Kaupert, Michael, and Irene Leser. 2014. Hillary’s Hand: On Contemporary Political Iconography. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Manemann, Thilo. 2021. “Terrorwave – Aesthetics, Language and Cultural Codes.” belltower.news, 17 February. Accessed 29 August 2025. https://www.belltower.news/schwerpunkt-rechtsterrorismus-terrorwave-aesthetik-sprache-und-kulturelle-codes-111635/.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 2009. “Four Basic Concepts of Image Science.” In: Image Theories – Anthropological and Cultural Foundations of the Visualistic Turn, ed. by Klaus Sachs-Hombach, 319–27. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp.

Molloy, Joshua. 2023. “Terrorwave: The Aesthetics of Violence and Terrorist Imagery in Militant Accelerationist Subcultures.” gnet-research.org, 5 April. Accessed 29 August 2025. https://gnet-research.org/2023/04/05/terrorwave-the-aesthetics-of-violence-and-terrorist-imagery-in-militant-accelerationist-subcultures/ (Stock Photography).

Nolte, Thomas. 2024. Stock Photography. Berlin: Wagenbach.

Ramsauer, Sandra. 2025. “500 Polizisten: Opernball wird Hochsicherheitszone.” krone.at, 26 February. Accessed 29 August 2025. https://www.krone.at/3704522.

Richard, Birgit. 2003. “World Trade Center Image Complex + ‘shifting image’: On the magic of the technical image.” Kunstforum International 164: 36-73.

Schneider, Frank. 2025. “Islamists threaten terrorist attack on Oktoberfest.” bild.de, 15 January. Accessed 29 August 2025. https://www.bild.de/news/inland/islamisten-drohen-mit-terror-anschlag-auf-das-oktoberfest-6787f3b948d3930c6fd0aadf.

Schneider, Pablo. 2014. “Political Iconography.” In: Image and Method: Theoretical Backgrounds and Methodological Procedures in Image Science, ed. by Netzwerk Bildphilosophie, 331–38. Cologne: Herbert von Halem.

Terrorwave. n.d. belltower.news. “Lexicon: Terrorwave.” Accessed 29 August 2025. https://www.belltower.news/lexikon/terrorwave/.

trackingterrorism.org. n.d. “About.” Accessed 29 August 2025. https://trackingterrorism.org/about/.

@TRACTerrorism. 2025. “[Tweet from 12 January 2025].” X (formerly Twitter). Accessed 29 August 2025. https://x.com/TracTerrorism/status/1878501164196745483.

Warnke, Martin. 2010. „Political Iconography.“ In: Iconography – New Approaches to Research, edited by Sabine Poeschel, 72-85. Darmstadt: WBG.

Zacharias, Wolfgang. 2012/2013. „Media and Aesthetics.“ kubi-online.de, 2012/2013. Accessed 29 August 2025. https://www.kubi-online.de/artikel/medien-aesthetik.

Image index

Figure 1: @TRACTerrorism. 2025. „[Tweet from 12 January 2025].“ X (formerly Twitter). Accessed 29 August 2025. https://x.com/TracTerrorism/status/1878501164196745483.

Figure 2: Joshua Molloy. 2023. „Terrorwave: The Aesthetics of Violence and Terrorist Imagery in Militant Accelerationist Subcultures.“ gnet-research.org, 5 April. Accessed 29 August 2025. https://gnet-research.org/2023/04/05/terrorwave-the-aesthetics-of-violence-and-terrorist-imagery-in-militant-accelerationist-subcultures/.

Figure 3: n.n. n.d. n.t. filmposter-archiv.de. Accessed 29 August 2025. https://www.filmposter-archiv.de/filmplakat.php?id=25612.

Figure 4: No author, no date, no title. filmposter-archiv.de. Accessed on 29 August 2025. https://www.filmposter-archiv.de/filmplakat.php?id=25785.

Figure 5: Jackson Walker. 2024. „‚You are next‘: Pro-ISIS group creates poster targeting US Capitol.“ Thenationaldesk.com, 6 September. Accessed 29 August 2025. https://share.google/images/ahtLzAlQ7VErqAMoL.

Figure 6: @rbb24 (Instagram). 2025. Post from 22 March. Accessed on 29 August 2025. https://www.instagram.com/p/DHfjAgfuLEC/?img_index=1.

Figure 7: n. a. n.d. „A hand holds a pistol and points it at the camera, black background. Accessed on 29 August 2025. https://www.westend61.de/de/foto/FSIF00661/eine-hand-haelt-eine-pistole-und-richtet-sie-auf-die-kamera-schwarzer-hintergrund.

[1] hereinafter also referred to as „collage“

[2] The quotes in this text have been translated from German into English by the Violence Prevention Network team.

[3] Terrorwave refers to a visual aesthetic found in online circles interested in right-wing terrorism (see the entry „Terrorwave“ in the bibliography of this article).

[4] Glitch aesthetics refer to image errors in digital media, such as distortions of a motif on a screen.

[5] In productions that feature the aesthetics of ‚tacticool‘, the subjects wear military clothing or equipment and carry replica firearms. The cool performance of the martial is central to this.