The case of the German „Reichsbürger“ and implications for P/CVE research

BY Maximalian Ruf und Dr. Dennis Walkenhorst,

first published At https://www.hedayahcenter.org/resources/reports_and_publications/researching-the-evolution-of-cve/

Sovereign Citizens, Freemen on the Land, Reichsbürger – names may differ, but the essence seems to remain the same. More and more countries around the world witness a number of their citizens claiming a distinctive kind of “ego-centered” sovereignty that, in its own logic, permits them to disobey social conventions as well as any kind of state authority. Besides from refusing to pay taxes, the creation of fake documents or their often bizarre (media) appearances, a more sinister aspect is overshadowed: the seemingly increasing use of violent means, especially against law enforcement officers. From a global perspective, obvious similarities between different kinds of sovereingists indicate that a new kind of extremism is appearing on the horizon.

Since sovereignism as such is an under-researched topic entailing a clear lack of empirical studies, this article is mainly based on secondary literature analysis and only aims to provide a first impulse for studying this field from a new and comparative perspective. Therefore, the case of the German “Reichsbürger” will be delineated and briefly differentiated from other known forms of sovereignism. Then, the case of sovereign citizens in the United States will be explored. The overarching objective of this exercise is to analyze if existing conceptualizations of different forms of extremism hold value as analytical frameworks to understand, study, and counter the highly under-theorized phenomenon that this article will define as “ego-centered sovereignism.” The analysis will show that while similarities and clear loans from better-known forms of extremist ideologies do exist, these frameworks seemingly fail to capture the essence of this new complex. We will therefore introduce a provisional theory-based definition for ego-centered sovereignism as a new global form of extremism that might be better suited to the phenomenon. Finally, implications for the practical P/CVE work will be drawn.

The Case of the German “Reichsbürger”

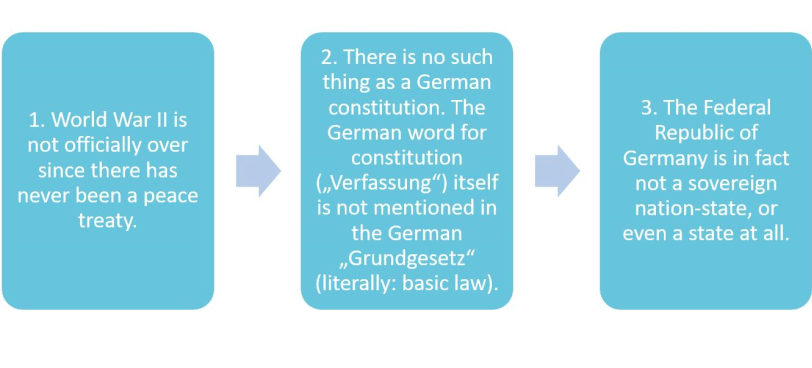

In Germany, sovereignism is mainly associated with one term: Reichsbürger. The term (literally: citizens of the “Reich”) refers to the ideology as well as the arguments used by some of the most curious German sovereignists, who, in principal, see themselves not as citizens of the Federal Republic of Germany but of a “German Reich” (Hermann, 2018, p. 7). While subgroups may vary significantly with regards to their exact beliefs and the conclusions they derive from them, most can agree on some key pillars of their ideology. This includes the belief that the “German Reich”, to which they claim to belong, subsists within either the borders of the former German Empire, or the German borders of 1937. Based on the supposed continued existence of some sort of “Reich”, Reichsbürger fundamentally deny the status of the Federal Republic of Germany (German acronym: BRD) as the legitimate successor state to the German Reich from 1949 onwards. Therefore, they do not accept any state authority derived from the Federal Republic (Hermann, 2018, pp. 7-10; Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, n.d.). This very basic ideological skeleton is mainly built on three claims and supposed arguments:

All of these so-called arguments are based on the conspiracy-belief driven idea that a sinister power is aiming tosuppress Germany and the German people by every means possible. More often than not, Jews are directly named as the driving force behind this, and in cases in which Jews are not referred to directly, anti-Semitic codes are used to obliquely reference them (Hermann, 2018, p. 10; Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, n.d.). For example, they produce so-called research to construct a Jewish heritage of current and former BRD politicians and leaders. One of these alleged discoveries showed that former chancellor Helmut Kohl was Jewish and that current chancellor Angela Merkel is in fact his daughter (see the argumentation of Norbert Schittke: ZDF heute-show, 2016). This is also part of the motivation behind the use of terms like “the Rothschilds” and other anti-Semitic codes when talking about decision-makers in German politics (ZDF heute-show, 2016; Hermann, 2018, pp. 7, 9).

With regard to the legal status of present-day Germany as we know it, among Reichsbürger, a number of opinions and different ideas exist on what the Federal Republic of Germany actually is. For some, it merely refers to a territory still occupied by the Allies since World War 2 (or sometimes even World War 1) (Hermann, 2018, p. 8). Others claim that the BRD is actually a commercial enterprise, the BRD GmbH,[1] and that Germans are not citizens but rather employees of that company (Hermann, 2018, p. 33; Deutsche Anwaltsauskunft, 2018). This latter claim is based on the fact that the title of the German government-issued identification cards is Personalausweis, which sovereignists interpret as “personnel identification”. Here again, personnel meaning employee. In fact, in the context of the German identification card “Personal” simply indicates that it is associated with an individual person, as in “personal identification”. This is but one example of the creativity which Reichsbürger often leverage for their conspiracy-ideology-based arguments.

Sociological, psychological, and demographic characteristics

When it comes to gaining deeper knowledge on sociological, psychological, and demographic characteristics of the Reichsbürger, there are almost no empirical sources or datasets that can be utilized. An exception are the insights of the intelligence agency of the German state of Brandenburg that were published in a “handbook” (Keil, 2017). This handbook, in combination with exploratory interviews with experts in the field, is one of the main sources for the following segment. It is, however, important to point out that the interviewees do not constitute a representative sample.

The demographic structure of the cases that were identified by intelligence agencies in the state of Brandenburg shows that there are around 80% male and 20% female followers of Reichsbürger ideologies. The average age of this group is around 50 years (Keil, 2017, p. 60f), which, in combination with the fact, that they had not come forward as Reichsbürger in the previous decades, could indicate that the process of radicalization occurs in the second half of life. It is important to draw attention to this aspect, since radicalization processes and engagement in crime or extremist groups typically occurs at an earlier age, at least this is true for other forms of politically or religiously motivated extremism (e.g., Carlsson et al., 2020, p. 74). The Reichsbürger identified in the Brandenburg “survey” usually live in social isolation with very few contacts outside their close family. Financially, they are often in debt, in many cases even bankrupt. For a lot of them, the only social interactions they regularly engage in are with their creditors, the judicial system, local authorities, or law enforcement (Keil 2017, p. 100). These encounters seem to become increasingly violent or at least aggressive as the Reichsbürger view officials such as police officers, judges, but also regular administrative clerks as active parts of a conspiracy directed against them and tend to escalate their aggression and eventually use of violence over the years (Keil 2017, p. 60ff).

An explorative psychological analysis of the same group (individuals considered to be Reichsbürger by the state of Brandenburg) demonstrated similar diagnoses of narcissism, schizophrenia, and paranoia are diagnoses among this subset in comparison to the general population. The same is true for different kinds of neuroses (Keil, 2017, p. 71ff). Hence, mental health issues seem to play an important role in a disproportionately large number of cases from this particular group of Reichsbürger. While these findings cannot be generalized, P/CVE work directed at this subgroup of Reichsbürger needs to reflect this characteristic of their target group in its programming.

As mentioned, it is questionable as to how representative these insights and numbers from the state of Brandenburg are for the broader German context, even more so for similar phenomena internationally. They are however, from a qualitative perspective, the best numbers available at present and may give first insights on what factors should be considered in comparative studies in the future. Nevertheless, it is important to notice that people that are now commonly referred to by the term Reichsbürger also constitute a diverse group. In his 2018 book “Eine Reise ins Reich” (“A Journey to the Reich”), Tomas Ginsburg explores this diversity of the movement by infiltrating a group of Reichsbürger. Although isolated older men indeed seem to constitute a significant part of most sub-groups, he finds people from all age groups as well as all social backgrounds to identify with these ideologies.

Sovereignists, Self-Administrators and Reichsbürger – Delineating Various Forms of Sovereignism in Germany

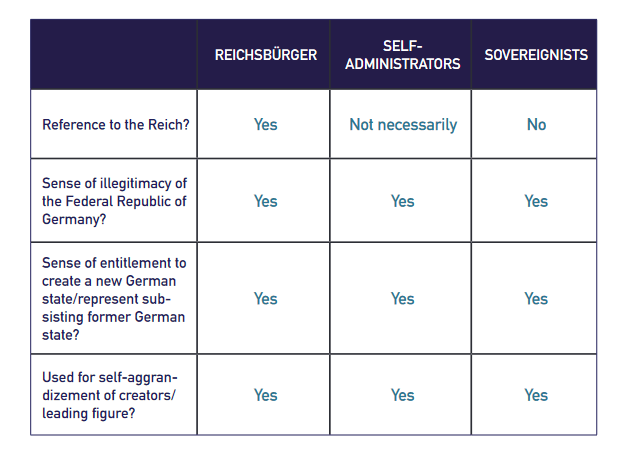

As previously noted, various forms and variations of what is commonly referred to as Reichsbürger exist across Germany. The federal domestic intelligence agency (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz; BfV) differentiates between two major strands of the phenomenon: “self-administrators” and “Reichsbürger” (literally: citizens of the Reich) (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, n.d.). As described above, the latter claim citizenship of a form of the former German Reich, sometimes in its form of the German Empire (until 1919) or Germany of 1937. Self-administrators, on the other hand, do not necessarily refer to the historical forms of the German nation state, but rather declare their own nations by announcing their personal “withdrawal” from the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesrepublik Deutschland; BRD) while designating their own homes or other properties as independent, sovereign nations (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, n.d.). Another way to categorize these different phenomena was proposed by Hermann (2018), who introduces the overarching terms of Reichs-ideologists or Reichs-ideological milieu with four different sub-milieus:

The first sub-milieu mainly strives to re-establish Nazism and the so-called Third Reich, while the second – the infamous Reichsbürger – believe that a form of the Reich in fact continues to exist, World War II (or even WWI) never actually ended, and that Germany in the current form of the BRD is an illegal construct (Hermann, 2018, p. 8). While these two subsets generally refer to a Reich of some form, the latter two notably do not. Self-administrators claim that the BRD is an illegitimate state and therefore feel entitled to declare their own, sovereign nations often in the form of imagined princely states or kingdoms (Hermann, 2018, p. 8). Most often the nation-defining individuals declare themselves rulers of these new states. Similarly, the fourth subset, sovereignists, believe that the current German nation state lacks legitimacy and is not a sovereign, independent nation. However, in contrast to the other forms, sovereignists neither presume the subsistence of a previous Reich, nor seek to establish entirely new states, but instead aim to make Germany as it is a sovereign nation again (Hermann, 2018, p. 8).

Hermann (2018) categorizes all four subsets under the term Reichs-ideologies. And yet, the latter two phenomena (self-administrators and sovereignists) do not seem to fit that specific term, as none of them refers to the concept of a German Reich. Based on this, a classification as Reichs-ideologies does not hold analytical value. The element that instead seems to be inherent to the two categories identified by the BfV (self-administrators, Reichsbürger) and the latter three identified by Hermann (Reichsbürger, self-administrators, sovereignists), is a sense of illegitimacy of the current German nation state paired with a feeling of entitlement as to the creation and/or representation of (new or old) forms of states within Germany’s current or former borders, independent from the current German authorities (see figure 1). Based on this, and on the fact, that while some commonalities exist among many of them, most German Reichsbürger, self-administrators and sovereignists have not succeeded in establishing larger movements or even groups of significant sizes, it appears these ideologies and resulting “nations” often serve as vessels for the self-aggrandisement of their creators. The one feature unifying all of them, is therefore not the reference to a Reich, but rather the fact, that they all adhere to a form of ego-centered sovereignism.

The following sections will explore, if this particular essence can be identified within similar ideologies and groups around the globe, which would mark ego-centered sovereignism a global phenomenon – and a global threat.

A Global Phenomenon?

Although the idea of the German Reichsbürger appears quite unique, some elements seem to exhibit surprising similarities to groups in other national contexts. This is true not only for the functional elements of the ideology, such as the ego-centered essence of these beliefs, but also for demographics and even psychological profiles.

Apart from the Austrian version, dubbed Staatsverweigerer, or state-deniers, whose ideology is very similar to the German case (Das Gupta, 2019), the most obvious are the infamous “Sovereign Citizens” in the United States, Canada, and even Australia (Hodge, 2019; Baldino & Lucas, 2019). Similarly inclined to conspiracy theories, paranoia and, most importantly, avid anti-governmental sentiments like the German Reichsbürger and other forms of sovereignists, they seem to have first appeared in the 1970s and 1980s. However, only in the years following the financial crisis of 2008 did they assume a more prominent role, at least in the American context (Hodge, 2019). While the precursor groups of the contemporary American Sovereign Citizens movement, such as “Posse Comitatus,” were initially often perceived as an extreme form of the anti-tax movement, aiming to limit the US American federal government’s influence on the financial and land properties of ordinary citizens, their apparent ideological similarities and the respective cross-referencing of arguments and ideas of openly far right militia groups, or racist movements like “Christian Identity” necessitated reconsideration of these assumptions (Hodge, 2019). Soon, the movement became to be viewed as being predominantly far right.

Today, Sovereign Citizens have become a widely public phenomenon. On YouTube, one can find numerous videos mocking their often bizarre court appearances or celebrating police officers already used to their made-up arguments and fake driver’s licenses (e.g., DDS TV, 2020; Van Balion, 2018; Lane Meyer 2017). As Berger (2016, p. 3) has outlined, the most important pillar of contemporary sovereignist ideology in the United States is based on an alternative understanding of American history. Centered around the 1868 14th Amendment, designed to award citizenship to former slaves, sovereignists believe that this created a form of second class citizenship and that the United States in general are no longer a constitutionally governed republic (Ibid, pp. 3-4). However, in their worldview a common law, derived from the original constitution or even the bible, exists, which supersedes the illegitimate legal framework of the current United States, which, in fact, are run by bankers who overthrew the legitimate government in secret and transformed it into a corporation, thus binding US citizens by a new set of now commercial laws (Ibid, p. 4). This illegitimate system, according to their beliefs, has created “fictitious persons” (often named in all capital letters on official documents such as driving licenses, etc.), which are then associated with the real “lawful being,” as which Sovereign Citizens identify themselves (Hodge, 2019; Berger, 2016, p. 5). Through a “declaration of sovereignty,” they aim to dissociate themselves from the “fictitious person” and everything associated with it and claim the rights and privileges of a citizen under common law (Berger, 2016, p. 5). Similar to the cases studied in Germany, sovereignist ideology in the United States often seems to appeal to persons, who have fallen to financial problems (Berger, 2016, p. 5), and for whom the ideas of sovereign citizenship may appear like a means out of debt.

While the basic framework of contemporary sovereign citizens in the United States does sound similar to that of sovereignists and Reichsbürger in Germany (including absurd reinterpretations of historical facts) the assumption that the government is illegitimate and even a corporation, conspiracy theories and anti-Semitism, another core features stands out as surprisingly similar: While a core ideological skeleton unites them in principle, so does their tendency to fill the gaps with individualistic themes, based on their own personal ideas (Berger, 2016, p. 3), making this a highly diverse scene rather than one unified movement. Sometimes individual figures stand out, advocating for their own interpretations and attracting a certain following, but in general, similar to the cases in Germany, this type of sovereignism seems to appeal to persons looking for a framework in which they can fulfill their own, ego-centered aspirations at leadership, truth, and wisdom, making them distinct from a majority of “ignorant sheep.”

These similarities are striking at first view and surely deserve deeper investigation in terms of comparative studies. While this article can only take a comparative view in a precursory way, the following section will explore how one might define violent ego-centered sovereignism as a distinct type of extremism, prevalent in many countries around the globe.

Defining violent ego-centered sovereignism

Existing conceptualizations of sovereignism appear to lack clarity or are only able to capture elements, rather than provide a comprehensive analytical framework. Astonishingly, there have not been many efforts that aim at comparing international cases of sovereignism and related phenomena until today. Furthermore, most of the case studies that exist are merely descriptive, focusing on the articulated ideology and/or specific arguments, and lack any theoretical foundation. For example, there are no sociological studies that focus on the similarities between sovereignist phenomena in different countries. In addition, near to no research has been conducted to answer the question what specifically distinguishes sovereignism from other forms of extremism. Oftentimes, sovereignism is just assumed to be another form of the far right, due to certain overlaps in ideologies and persons (e.g., Hodge 2018; Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, n.d.;). Similar to comparative studies, psychology has, until today, been largely neglected as a discipline that has the potential to generate important insights into the world of ego-centered sovereignists. One of the few exceptions is the explorative analysis of individuals in the state of Brandenburg that Jan-Gerrit Keil (2017) provides. While these types of (non-representative) explorative psychological analyses are definitely promising to understand individual cases in regional contexts, a broadening of the perspective to the international scale is nevertheless necessary to advance the understanding of this complex phenomenon. In doing so, a sufficient number of cases could be included into the analysis and therefore produce a broader empirical foundation for (psychological) analysis.

As mentioned, this introductory article can only aim at providing first impulses towards a more accurate definition of the phenomenon. To sketch such an initial definition, it is helpful to first explore differences and commonalities with other familiar and previously defined forms of extremism.

Essential differences to religious or political extremists

Oftentimes, ego-centered sovereignism has been linked to the far right. And on personal and/or institutional levels, connections to the far right scene seem to be obvious in many cases especially in Germany and in the United States (Hodge 2018; Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, n.d.). However, remarkable differences between politically and religiously motivated extremism and ego-centered sovereignism can be identified when taking into account how they perceive and interpret the roles of politics and religion in society.

Political extremists (right and left wing) fundamentally challenge the (democratic) system, but they do not challenge the value of political authority as such, meaning its essence. Their aim is a different kind of political authority (fascism, communism, authoritarianism, i.e.) – they want to change the way the political system works, meaning the way collectively binding decisions are made, but not the role of the political system itself. Religiously motivated extremists, in contrast, aim at replacing the political system with one based on their religious doctrines. They usually try to reestablish religion and literal interpretations of religious texts as the only sources for collectively binding decisions. The one legitimate authority, in their eyes, is God. In this sense, laws can only be derived from religious sources, which puts religion (resp. religious scholars) in the position of lawmakers.

These different perspectives on how extremists view the role of politics and religion in producing collectively binding decisions are key in understanding the essential difference to ego-centered sovereignism. In contrast to known forms of extremism, ego-centered sovereigntists largely do not seem to accept political or religious authority whatsoever. The center of their attention is first and foremost the self, the ego. The only legitimate source of authority is, implicitly or explicitly, their own individual person, which is then consequently no longer obligated to follow any collectively binding decision that was produced politically or religiously. In this sense, ego-centered sovereignism is ideologically much closer to anarchism than to any other political or religious extremism. Additionally, ego-centered sovereignism should be interpreted as a phenomenon that, unlike other extremisms, is in its essence post-modern. As processes of individualization accelerate even after ongoing modernization and globalization, individualism poses a challenge especially when it comes to processes of identity formation. Analysis that take a post-modern constellation into account might be even more suited to explain what makes ego-centered sovereignism with its absolute individualism attractive nowadays.

So while the numbers of identified followers of sovereignist ideologies seem to be constantly rising, the individualized sovereignists seem to fail at forming any coherent movement, unlike political or religious extremists. This inability to cooperate and create broader structures as a movement is inherently caused by the individualized nature of ego-centered sovereignism as an ideology but seems to also be supported by highly narcissist personalities as well as claims to absolute authority, as Keil (2017, pp. 86-87 has shown for the Brandenburg sample. While they refuse to accept political authority, they also refuse to accept any other individual authority (other than themselves), leading to the impression that the so-called Reichsbürger movement is not really a movement but more an accumulation of individual leaders without a high number of followers. This fact, again, highlights the seemingly ego-centered characteristic of many of these individuals, supporting the argument that at the core of most of these phenomena lies an inherently ego-centered sovereignism that seems to be much more similar to cults than to any kind of political or religious extremism.

Similarities to Cults

Cases observed in Germany seem to bear remarkable similarities to smaller cults and sects, as some authors have previously noted (see e.g. Rütten, 2016a; Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, n.d.; Rohmann, 2018, p.7; Hermann, 2018, p.15). Also, internationally, similarities between Sovereign Citizens and cults or cult-like groups have previously been identified (see e.g. Colacci, 2015; Southern Poverty Law Center, n.d.). The social structure of their groups as well as the special kind of self-empowerment the leaders apply is remarkably similar to what we know about cult structures. The patriarchal leader of small and tightly knit ego-centered sovereignist cells is in a comparable position as any cult leader (Hüllen/Homburg 2017, p. 42). Loaded language and milieu control, for instance, through the heavy use of highly complex, impossible to fully understand conspiracy theories, designed to keep the followers within the group and mindset, are tools of cults (Rohmann, 2018, p.9), that can also regularly be observed with groups of sovereignists. Sometimes, (former) members of such groups even try to use the cult-argument in their favor. In 2012, a supposed Reichsbürger in Germany, charged for the possession of large quantities of chemicals, which could have been used to build explosive devices, claimed to be the innocent victim of a cult, thus not responsible for his own actions (Rütten, 2016a).

One more prominent example, Peter Fitzek, declared himself king of the Kingdom of Germany and actually managed to attract a decent and financially capable following. At least 558 persons had handed over around 1.2 million Euros to him by 2014 (Rütten, 2016b). In addition, to enlarge the physical bounds of his so-called kingdom, he had his followers donate their own land possessions (Rütten, 2016b). During the earlier days of his endeavor, Fitzek charged his followers for seminars which he held (Rütten, 2016b). While he uses certain symbols and arguments commonly associated with the Reichsbürger scene, Fitzek, as apparently many others, is focused mainly on his personal self-aggrandizement by engaging in his own perceived right to declare sovereignty and himself as the ruler, rather than cooperating with others who hold similar views (Rütten, 2016b).

Similarly, to the case of Fitzek, Berger also notes individual “’gurus’ or ‘experts’” within the American Sovereign Citizen scene and highlighted the fact that certain groups and individuals seem to have created ways to financially profit off their followers, by, for example, hosting instructional seminars or selling pseudo-legal filing kits suited to the complex pseudo-legal processes in which they would have to engage (2016, pp. 5-6). Using their followers for personal financial gain based on a presumed all-encompassing authority of one singular authority figure has been one of the key elements of many prominent cults over the past decades.

While overlaps regarding followers and ideologies between ego-centered sovereignists and political or religious extremists do certainly exist, many of the mechanisms, especially the focus on self-aggrandizement and self-empowerment paired with the inability to cooperate beyond the fraudulent extraction of money from followers, appear to be more familiar from cult and cult-like groups. Therefore, and in order to understand the phenomenon properly and in all its facets, it might be worth taking a closer look at possible links and similarities to determine whether or not the current trend of portraying this type of ego-centered sovereignism as merely another subset of “the far right” is accurate.

Challenges for P/CVE

Usually, discussions with ego-centered sovereignists are the opposite of what one would call “productive”. Their aggressive, compulsive and often disabusing attitude makes it nearly impossible to reach common ground. While this is in essence true for every conspiracy theorist, the element of self-exaltation that ego-centered sovereignism obviously brings with it seems to add an extra layer of resistance towards other opinions as well as to ambiguity in general. While it seems to be much easier to initiate a first contact to ego-centered sovereignists than to other target groups, their level of indoctrination and missionary motivation is often significantly higher.

This is one of the reasons why working with ego-centered sovereignists for the purposes of prevention and deradicalisation brings many challenges. One of them is the age of the target group. Usually, radicalization processes take place at an early age (this is also why most prevention programs focus on target groups of 15-25 years). With ego-centered sovereignists, however, the opposite seems to be true. From what we know from the Brandenburg sample, many cases of ego-centered sovereignists seem to be older (white) men (Keil 2017, p. 100). As cynical as it may sound, when deradicalisation work usually focuses at making plans for the future and exploring options for a “healthy” life after distancing oneself from extremist groups and ideologies, this is not nearly as relevant to people in their late fifties or sixties than it is to “youngsters” that practitioners in deradicalisation typically work with.

Another challenge is the social isolation that some ego-centered sovereignists live in. Most deradicalization initiatives work with a systemic approach, meaning they include relevant persons from the social environment of the client in the work. This is especially important when it comes to any effort of reintegration or rehabilitation. With the target group of ego-centered sovereignists, however, a social network often is nearly non-existent or includes only very few close friends and/or family-members who themselves might be drawn to the ideology of ego-centered sovereignism, often as part of the made-up “government” that a patriarch created for his family. This is why the identification of persons who might be able to assist any deradicalization process is by far more challenging for cases of ego-centered sovereignism. Additionally, ego-centered sovereignists are often considered troublemakers in the eyes of the judiciary system as well as the public administration (Keil 2017, p. 56; Hodge 2019). This makes their involvement in rehabilitation processes challenging, especially when they already have been victims of the so-called paper terrorism conducted by an individual. [3]

The ideologies ego-centered sovereignists follow often seem absurd or at least obscure to the outsider. However, their fundamentally deep connection to conspiracy theories makes sovereignist ideologies attractive alternatives in light of the complexity and ambiguity of modern life. Believing in sovereignist ideology means having answers to all the big questions while at the same time leading to an individual self-exaltation as the (only) one knowing the “truth”. What comes with this is a massive reduction of complexity and a newfound position as a privileged, “enlightened” person. While deradicalization work usually focuses on identifying functional equivalents for what an extremist scene offers the individual, this kind of certainty and self-exaltation is extremely hard to replace.

Conclusion and implications for (future) P/CVE research

Throughout this article, we have argued that severe gaps in current research can be found when it comes to the case of ego-centered sovereignism. First and foremost, the phenomenon itself is in need of definitions as well as theory-based case studies. We need to understand what makes ego-centered sovereignism special – what drives these target groups and what functional differences as well as similarities to known extremisms are observable. Second, comparative studies are duly needed. We identify different forms of the phenomenon in many countries, for example Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Norway, Canada, the United States, and Australia, but until today, no comparative case studies have been conducted. The main focus of researchers is often on different kinds of obscure arguments ego-centered sovereignists use, but not on the psychological and sociological implications of their behavior and the phenomenon in general. This is why researchers who usually focus on descriptive studies of right wing extremism analyze ego-centered sovereignism as just another type of right wing extremism. Instead of merely echoing their arguments (the same thing the media does constantly), theory-based analyses of potential root causes, functional mechanisms, and dynamics are needed.

After understanding causes, mechanisms, and dynamics of the phenomenon, implications for P/CVE might be much easier to identify. What we know today is that the target group is at least challenging for P/CVE practitioners who try to engage with them. Although often interpreted as just another kind of extremism, tools and methods from working with right wing extremists do not necessarily prove to be effective with ego-centered sovereignists. This is why the development of innovative and specified tools and methods for working with this target group should be one of the main priorities of any future P/CVE research. As many P/CVE practitioners already articulated, radicalization at a later age and a deep-rootedness in conspiracy theories constitute challenges for other forms of extremism. So, the development of specified tools and methods for cases of ego-centered sovereignism might also benefit P/CVE in general. Furthermore, there seems to be a lot to learn from adjacent fields, especially cult studies.

References

Baldino, D. & Lucas, K. (2019). Anti-government rage: understanding, identifying and responding to the sovereign citizen movement in Australia. Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism, 14(3), 245-261.

Berger, J.M. (2016). Without Prejudice: What Sovereign Citizens Believe. George Washington University Program on Extremism. https://extremism.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs2191/f/downloads/JMB%20Sovereign%20Citizens.pdf

Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz. (n.d.): ‚Reichsbürger‘ und ‚Selbstverwalter‘[‚Citizens of the Reich‘ and ‚self-administrators‘].https://www.verfassungsschutz.de/de/arbeitsfelder/af-reichsbuerger-und-selbstverwalter/was-sind-reichsbuerger-und-selbstverwalter

Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (2019): Verfassungsschutzbericht 2018 [2018 Annual Report on the Protection oft he Constitution]. Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat. https://www.verfassungsschutz.de/de/oeffentlichkeitsarbeit/publikationen/verfassungsschutzberichte

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (n.d.). Glossar: Reichsbürgerbewegung [Glossary: Reichsbürger Movement].http://www.bpb.de/politik/extremismus/rechtsextremismus/173908/glossar?p=69

Carlsson, C., Rostami, A., Mondani, H., Sturup, J., Sarnecki, J., & Edling, C. (2020). A Life-Course Analysis of Engagement in Violent Extremist Groups. The British Journal of Criminology, 60(1), 74–92. https://academic.oup.com/bjc/article/60/1/74/5545274

Colacci, M. N. (2015). Sovereign Citizens: A Cult Movement That Demands Legislative Resistance. Rutgers Journal of Law and Religion, 17(1), 153-165. https://lawandreligion.com/sites/law-religion/files/Sovereign-Citizens-Colacci.pdf

Das Gupta, O. (2019, January 26). Die wirre Welt der Monika U. [The confused world of Monika U.]. süddeutsche.de. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/oesterreich-staatsverweigerer-reichsbuerger-hochverrat-1.4304432.

DDS TV. (2020, March 22). Sovereign Citizen vs Cops / Messing with the Wrong Cops #5 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xRVndBmgXRg

Deutsche Anwaltsauskunft (2018, May 18). Faktencheck: Ist Deutschland eine GmbH?[Fact Checking: Is Germany a GmbH (roughly equivalent Ltd.)]. https://anwaltauskunft.de/magazin/gesellschaft/staat-behoerden/ist-deutschland-eine-gmbh?full=1

Extra 3. (2016, October 27). Christian Ehring: Reichsbürger in Deutschland (1) [Christian Ehring: Reichsbürger in Germany (1)][Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rdEvOKqrcvI

Hermann, M. (2018). “Reichsbürger” und Souveränisten – Basiswissen und Handlungsstrategien [„Reichsbürger“ and Sovereignists – Basic Knowledge and Strategies for Action]. Amadeu Antonio Stiftung. https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Reichsbuerger_Internet.pdf

Hodge, E. (2019). The Sovereign Ascendant: Financial Collapse, Status Anxiety, and the Rebirth of the Sovereign Citizen Movement. Frontiers in Sociology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00076/full

Hüllen, M. & Homburg, H. (2017). “Reichsbürger” zwischen zielgerichtetem Rechtsextremismus, Gewalt und Staatsverdrossenheit [„Reichsbürger“ between Goal-driven Right-wing Extremism, Violence and Disenchantment with the State]. In D. Wilking. (Ed.), „Reichsbürger“(13-38). Ein Handbuch. Demos, Brandenburgisches Institut für Gemeinwesenberatung, Potsdam.

Keil, J.G. (2017). Zwischen Wahn und Rollenspiel – das Phänomen der “Reichsbürger” aus psychologischer Sicht [Between Delusion and Roleplaying – The „Reichsbürger“-Phenomenon from Psychological Perspective]. In: D. Wilking. (Ed.). „Reichsbürger“ (39-90). Ein Handbuch. Demos, Brandenburgisches Institut für Gemeinwesenberatung, Potsdam.

Lane Meyer. (2017, April 29). Judge Has No Time for Sovereign Citizen’s Nonsense [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GBVbK9Ig7Bs

Mudde, C. (2019). The Far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity Books.

Pitcavage, M. (1998). Paper Terrorism’s Forgotten Victims: The Use of Bogus Liens against Private Individuals and Businesses. Militia Watchdog Special Report 1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20020918011634/http://www.adl.org/mwd/privlien.asp

PULS Reportage. (2016, October 21). Die Verschwörungstheorie der Reichsbürger – und was Xavier Naidoo damit zu tun hat [The Reichsbürger’s Conspiracy Theory – and What Xavier Naidoo Has to Do With It] [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6fkOfenEsXk

Rütten, F. (2016a, October 20). Was sind Reichsbürger und wie begründen sie ihre Thesen?[What are Reichsbürger and How Do They Prove their Theses?].Stern. https://www.stern.de/panorama/stern-crime/reichsbuerger–was-sind-das-fuer-menschen-und-worauf-fussen-ihre-thesen–7109172.html

Rütten, F. (2016b, April 8). Der Mann, der sich ‚König von Deutschland‘ nennen lässt [The Man Who Lets Himself be Called „King of Germany“].Stern. https://www.stern.de/panorama/weltgeschehen/peter-fitzek–der-mann–der-sich–koenig-von-deutschland–nennen-laesst-6786460.html

Sabinsky-Wolf, H. (2016, October 19). Wer ist der “Reichsbürger” aus Mittelfranken?[Who is the „Reichsbürger“ from Middle Franconia]. Augsburger Allgemeine. https://www.augsburger-allgemeine.de/bayern/Wer-ist-der-Reichsbuerger-aus-Mittelfranken-id39446942.html

Siebold Filmproduktion, D. (2016). Der amtierende Reichskanzler – Dokumentarfilm (2003) [The Sitting Chancellor of the Reich][Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTXx47bZccM

Southern Poverty Law Center. (n.d.). Sovereign Citizens Movement. https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/sovereign-citizens-movement

Spiegel Online. (2016, October 20). Anlass zur Besorgnis gab es nicht [There was no Cause for Concern]. https://www.spiegel.de/panorama/justiz/reichsbuerger-wolfgang-p-buergermeister-sah-keinen-anlass-zur-besorgnis-a-1117533.html

Van Balion (2018): Sovereign Citizen Arrested [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ir0IBD2L8ro

Welt (2017): Reichsbürger muss wegen Polizistenmords lebenslänglich in Haft [Reichsbürger Sentenced to Life in Prison for the Murder of a Police Officer]. https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article169938165/Reichsbuerger-muss-wegen-Polizistenmords-lebenslaenglich-in-Haft.html

ZDF heute-show. (2016). Carsten van Ryssen trifft den Reichskanzler Norbert Schittke – heute-show vom 02.12.2016 | ZDF [Carsten van Ryssen Meets the Chancellor of the Reich, Norbert Schittke] [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7oy7g7HGeks

[1] GmbH is a legal form for a commercial enterprise in Germany, similar to an American Limited liability company.

[2] Here, “right-wing extremist” was used as a term in order to most accurately translate the original German “Rechtsextremisten”. In the following, we will use the term “far right” instead, which is understood as the overarching term for the right-wing political sphere beyond the mainstream right, itself divided into the radical right and the extreme right (for a more detailed discussion of these categories, see also Mudde, 2019).

[3] Paper terrorism is defined as “the use of bogus legal documents and filings, or the misuse of legitimate ones, to intimidate, harass, threaten, or retaliate against public officials, law enforcement officers, or private citizens.” (Pitcavage 1998)